Visuals for Talking About the Brain

Helping kids understand their learning differences doesn’t happen at the feedback session – it’s an ongoing conversation throughout the assessment.

In a previous post, I shared some strategies I’ve learned to start the conversation before I’ve met the child. In this post, I wanted to share a visual tool I’ve been using to help students buy into – and get excited about – the assessment process.

Helping Kids Ask Their Own Assessment Questions

In an ideal world, the testing process is not something we do to a child to find out what’s not working, but something we do with a child to find out what will work.

I’ve found the best way for me to build this kind of collaborative relationship during testing is to encourage kids to ask their own assessment questions*. Coming up with a question the child cares about gives testing a purpose, and lays the foundation for a feedback session that will actually sink in.

This all makes great intuitive sense; however, getting a child to ask a referral question proved to be more challenging than I thought.

How do we help kids get curious about the stuff they spend most of their life trying to avoid?

When I first started asking kids what they wanted to know about their learning, I typically got some version of “I don’t know” or “Nothing – everything is fine.”

I started to realize that kids often don’t have the words to describe what’s going on, and even if they do, they’re often too scared to share it.

After a few years of refinement, I’ve found a 3-step introduction to testing that helps me get past these barriers:

- Creating a shared vocabulary

- Identifying what they’re already good at

- Asking what they want to get better at next

1. Building a Shared, Brain-Based Vocabulary

I love talking about the brain during feedback sessions; however, like most things I’m learning about feedback, I’ve realized I have to start much earlier.

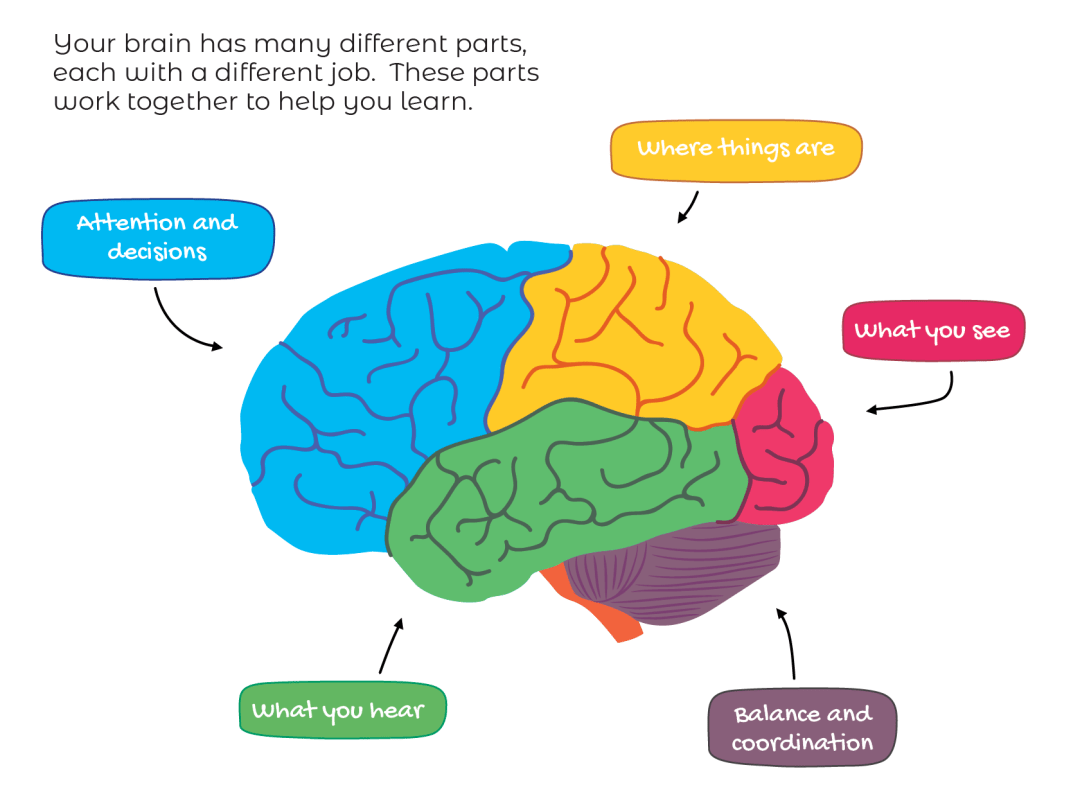

So, I’ve started using the brain diagram below from the beginning. On the first day of testing, my goal is to give the child some basic brain-based vocabulary, so that they can start talking about their own brains and asking questions.

For younger children, I describe the general function of each lobe of the brain. For older children, I might write in the formal names, or add in other areas that are relevant to our conversation (e.g. the motor strip for writing, or Wernicke’s area for comprehension).

This approach turns the assessment into a cool science discovery project, instead of a just bunch of tests.

By way of introduction, I might say something like:

“The brain has lots of different parts, all working together to help you understand what you see and hear, know where things are, pay attention, make good decisions, and coordinate your movements.

As we work together, every activity we do will help us discover how these parts work together to solve different types of problems.”

2. What Used to Be Hard?

Next, we talk about what the child likes to do – their strengths and interests. This way we get to practice using their new-found brain-based language to describe what’s really working well for them.

Now the child has the words to start asking a question – any question – about the brain, like:

“Which parts of the brain helps me play Minecraft?!”

Often their questions aren’t immediately related to the issue that brought them in, but they become the child’s reason for testing. What can the tests tell us about why you enjoy video games, or dancing, or math, or talking to friends?

But even when I gave kids the vocabulary, I still found that many were not able to talk about the things that were hard. As soon as I mentioned the parents’ referral question (e.g. reading), they would get defensive and tell me why it’s not actually a problem.

Many kids are simply scared we’re going to find out something is wrong with them.

To get past this, I started asking them if they could think of something that used to be hard, but is now pretty easy.

“When we try something new, it can take a while for the parts of our brain to figure out how to work together in just the right way. For example, when you were little you may remember that at first is was hard to…

But not anymore!”

This establishes that the brain is constantly under construction. There is nothing wrong, just skills that are trickier to build than others.

For those kids who struggle to come up with something, we often talk about learning to walk as a baby or learning the different levels of a video game.

Now we’re ready to talk about the next construction project.

3. What Would You Like to Be Easier?

At this point in the conversation the child has some basic brain vocabulary in their pocket, and we’ve highlighted how their brain has successfully overcome obstacles in the past. From here, it is much easier to ask:

“What is the next thing you’d like to get better at? What’s challenging about that now?”

This is where the child’s referral questions come from. Their lens has shifted from “what’s wrong” to “what can be better?” This makes it easier to figure out what they want to know.

Here are a few examples of questions that have come from this discussion:

- Why do my eyes get tired while reading but not while playing video games?

- Why am I good at geometry but can’t remember my times tables?

- How can I make writing more fun?

It should be noted that many times the thing the child wants to get better at has nothing to do with the parents’ or teachers’ referral questions. That’s just fine. Whatever they say is the place where we start.

An Ongoing Reference

I’ve found using the brain image above extremely helpful for inspiring a child to ask good referral questions and engaging them in the assessment process:

- It’s a concrete reference point we can return to over the course of testing

- It’s a fun product to show parents

- It tells the child exactly what will happen at the feedback session: we’re going to answer the questions they asked!

I hope you find this visual helpful for inspiring brain-based assessment questions from the children you work with! Please share with anyone else who may find it useful by sharing this post.

As always, let me know how else I can help!

*Assessment as a collaborative process stems from the research on Therapeutic Assessment as well as the Collaborative Proactive Solutions approach to helping children with behavioral challenges.